The latest AUKUS announcement ignited a furious debate. How should we weigh the risks and rewards of the plan for Australia to acquire nuclear-powered submarines? Critics, from former prime ministers to sceptical analysts, questioned the plan’s strategic efficacy, its opportunity cost, its feasibility, and its impact on Australian sovereignty. Well may these debates continue, but the intent is plain: to change the military balance of power in the region.

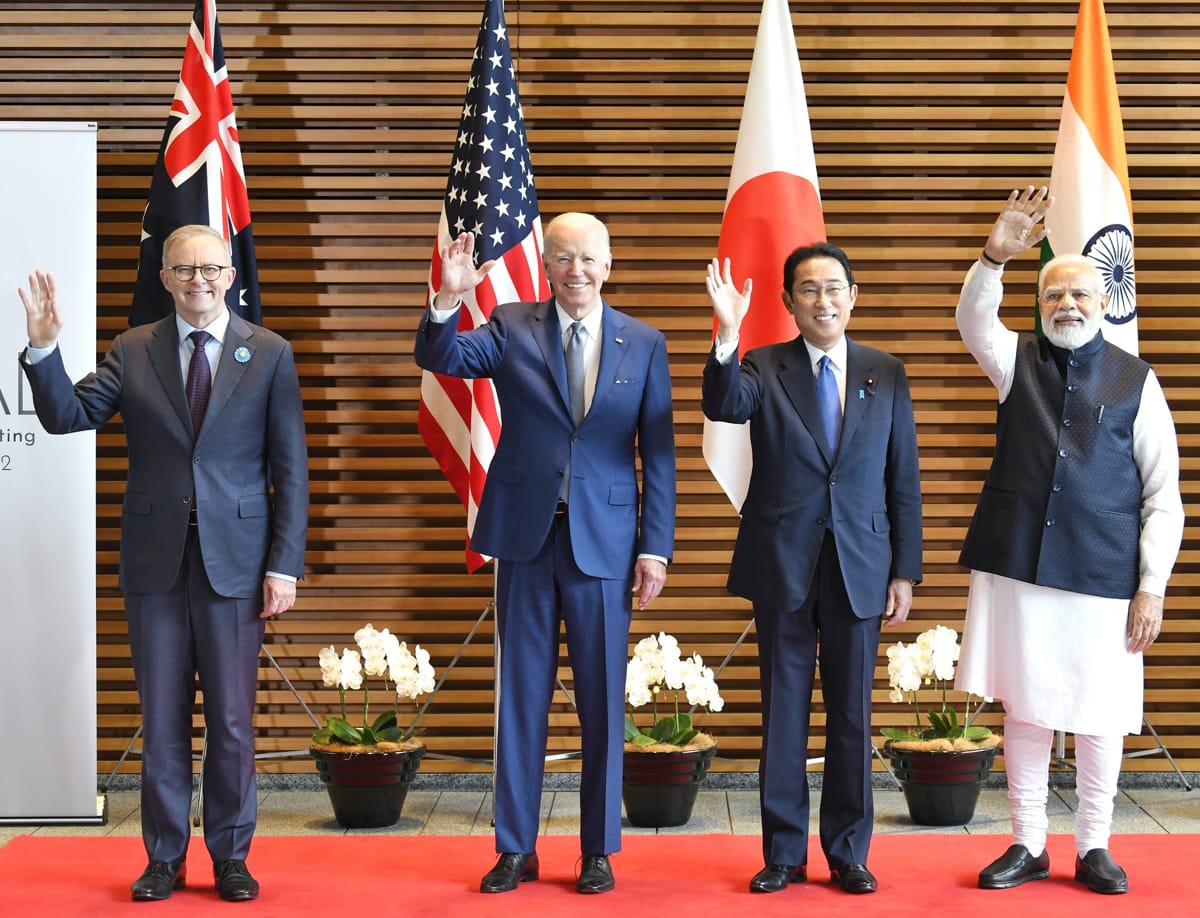

With that, AUKUS stands in bold contrast to another grouping of partners, the Quad, comprising Australia, India, Japan and the United States. It may now be time for the Quad to take some lessons from AUKUS.

In purpose and composition, AUKUS and the bilateral partnerships that underpin it can scarcely be compared to the Quad. The Australia-US alliance is a treaty-bound security pact resting on decades of trust and institutional connections. The Quad has no formal mandate, no military role, and brings together major powers that have only recently begun to consult on regional matters. The Quad cannot be expected to function like an alliance.

But if the Quad’s members decide to assume a security role in the region, they could learn something from the Australia-US alliance.

As part of a research project last year, my collaborators and I invited Australian government officials to study and role-play whether the Quad could deter Chinese aggression. In the “matrix game” we designed, the officials tried to dissuade Beijing mostly by signalling their displeasure in a range of ways. They issued statements clarifying their position, sent ships on patrol, and offered more statements. Conspicuously, they rarely sought to change the material balance of power to make aggression more difficult or costly. China, in that exercise, was undeterred and achieved its objectives.

In the absence of material effects, “cheap talk” may even send an opposite message. Signals without action lack credibility.

By contrast, the notable feature of the Australia-US alliance in recent years is its attempt to change the material balance of power in the region. Since US Marines began rotational deployments to Darwin a decade ago, the force posture initiatives by the United States and Australia plan to position fighter and bomber aircraft, ships and soldiers in Australia. Critics can and should debate the merits of each of these steps, but there is no denying they are changing facts on the ground – and, with AUKUS, under the water.

These material changes in military power are the types of action that would be necessary to deter a potential adversary from aggression. If they can reduce the chances that the aggressor could successfully pull off an attack at acceptable cost, they may force it to think twice. China, for example, will only be dissuaded from attacking Taiwan if it fears the military odds are stacked against it, or the overwhelming international response would scupper its “national rejuvenation”. Sternly worded letters will not do.

Sending signals designed to show resolve is an integral part of effective deterrence, but alone they are not enough. In the absence of material effects, “cheap talk” may even send the opposite message. Signals without action lack credibility. As in our matrix game simulation, they may convince the adversary it faces no real consequences, inadvertently green-lighting its plans for aggression.

If the Quad chooses to take on a deterrence mission, it could use a range of material actions, drawing inspiration from the Australia-US alliance. Over the long term, and most ambitiously, changing the material balance of power would involve its members building new military capabilities. AUKUS sets a high bar, but Australia’s recent Defence Strategic Review is expected to have likely recommended a host of other, more achievable modernisation initiatives.

Quad members could also shift the material balance quickly and cheaply by repositioning existing military forces. Quad members have valuable real estate that, with new access and basing arrangements, could significantly disrupt Chinese military planning. Australia’s Cocos Island, and India’s Andaman and Nicobar Islands, for example, both lie within tantalisingly close range of key chokepoints and China’s military facilities in the South China Sea.

This is a risky business. The Quad taking on a new military role would trigger political sensitivities, among its members and especially in the region. So delicate messaging would be of utmost importance. Indeed, new military activities undertaken by Quad members need not even be branded as Quad initiatives. Observers also fear that new capabilities or operational ties may constrain Australia’s future political choices. But the lack of those capabilities or integration would be even more constraining – lacking the military means to act would pre-emptively deny Australia the option to act if its political leaders so wished.

The Quad’s military preparations may also provide opportunities for China. Beijing’s intent to gain control over Taiwan, by force if necessary, is clear, abiding and immutable. But it could still exploit others’ military preparations as a pretext to make material preparations of its own. These are serious risks that demand consideration. But without risk, there can be no deterrence.

Source : TheInterpreter